‘Boston College Touts’ Threat Discussed in Dáil Éireann

Dáil Debate 13 May 2014

Ceisteanna – Questions (Resumed)

Full debate begins here: Taoiseach’s Meetings and Engagements

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Excerpts relating to Boston College oral history archive participants under threat:

Deputy Micheál Martin: In terms of the questions on the Ballymurphy murders, there is no doubt that innocent people were murdered by British soldiers in Ballymurphy in August of 1971. Forty-three years later, the official account has not been corrected and the families have been denied the right of being told exactly how these murders happened. The British Government, as the Taoiseach said, through the Northern Secretary, recently asserted that there should be no review of the murders because of what she called “the balance of public interest”. This goes to the nub of the ongoing detachment and mishandling of the peace process and reconciliation generally. It speaks of a policy that suggests that everything has been achieved, all the big things have been achieved and we do not need to deal with these issues. I met the Ballymurphy group some years ago and it seemed to me that, at the very least, an independent panel of investigators, with some international dimension attached to it, should have been established to report on the murders, such is the appalling nature of what happened.

It needs more than just the Taoiseach articulating here that it is very disappointing that the British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland said this. Was there any consultation between the Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade and the British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Ms Theresa Villiers, MP, prior to the decision not to set up a panel to investigate those murders?

While I strongly support the need for this, it equally has to be said that the family of Jean McConville is also entitled to justice and truth in respect of her murder a year later. Both cases show that different sides are trying to be selective in their approach to the past. The British Government will pursue one case but will say there is no need to deal with the murder of 11 people in 1971 because of some obscure balance of public interest reasons. Likewise, I do not believe one can deny the family of a mother of ten who was murdered in 1972 the right to truth, justice and information, and yet Sinn Féin would probably want that denied.

The breakdown of the Haass talks is related and the decision to take a hands-off approach to that up to now has failed. I see from recent comments that that has been accepted and that there is a need for intervention. What steps does the Taoiseach intend to take regarding the Ballymurphy question? How does he intend to get the British Government to change its mind on pursuing the establishment of an independent panel to investigate the murders?

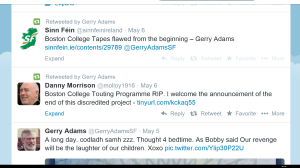

Regarding the Boston College tapes of interviews relating to the McConville case, a disturbing trend is emerging whereby those with anything to do with the Boston College project are being labelled as touts, and as greedy and reckless. A hate campaign is being developed by foot soldiers within the Sinn Féin movement, as far as I can ascertain, to target people. Regardless of whether one likes it, I believe the people involved in the Boston College project saw it as an historical project. They did not envisage the British prosecuting authorities seeking release of the tapes, Boston College being acquiescent, to say the very least, in opposing that until it was forced into a position where now certain tapes relating to the prosecution of that case have been released.

Now a hate campaign has developed where those responsible for conceiving the project and doing the interviews are being targeted in language that is very dangerous. The Taoiseach might have seen recent articles in which Mr. Ivor Bell is called the “Boston tout”. People are under pressure to ‘come clean’ about the contents of the controversial Boston tapes. It is very sinister and almost sets people up for attack. It makes people very insecure and anxious. There should be no toleration of it. It is extremely important that it is nipped in the bud and that all responsible people would deal with that. I ask for the Taoiseach’s comments on the implications of that. […]

The Taoiseach, Enda Kenny: […] As I understand this, the number of people who have been questioned about this is six or seven – Deputy Adams will know that – and that one of those is being charged with conspiracy by association. Whether that moves through to the PPS to a further stage is something that I cannot predict. I think everybody in this country is haunted by the picture of Jean McConville and a number of her children – that black and white photograph – which has appeared thousands of times over the years. I know from meeting people who have lost loved ones at sea or whatever, through a tragedy or just an accident, that a sense of closure, not being able to say where they are and who was responsible and that justice be seen to be done is very powerful.

I agree with a comment made by Deputy Martin in regard to the Boston College tapes that there seems to be a sort of campaign that these are not valid, authentic or real contributions. Somebody who knows something about this said to me that some of the contributors were either dependant on alcohol or requiring of substance use all the time. I suppose the old saying in vino veritas is still valid. These are part of, and a background to, the problem we have with the past and the legacy of what that means. I share Uachtaráin Higgins’s response, when commenting on this, I think, in Chicago, that nobody should be above law and that we cannot have one law for one and a different one for somebody else.

If the gardaí did not have the intelligence and communications they have available to them and the sharing of knowledge with the PSNI, this incident at Finnstown House recently could have been very serious, with the possibility of international repercussions for Ireland of the most serious kind, and the loss of life.

The issues arising over the last period in regard to the question of the past, parades and so on goes back to a comment made by the Tánaiste that there is a short opportunity after the electoral process is finished here and before the marching season gets into full swing in which we should perhaps refocus on what it is we may be able to do here. When I look at what is happening in Derry and I see the excitement, the expansion of the economy, the jobs being created and the view of the future where people really want to get on with the business of providing for their children, opportunities and so on, I see a difference between that and what is happening in places in Belfast. That is regrettable. I saw the television pictures, and Deputy Adams was involved. Perhaps there is an opportunity here to refocus, as two Governments, to help the Northern Ireland Executive and the parties in Northern Ireland. President Clinton said that we have to finish the job, it cannot be finished for them, it has got to come from inside and we have to give them all the encouragement we can. […]

Deputy Gerry Adams: […] I return to the issue of victims. I will conclude on this matter. Irish Republicans have acknowledged many times the hurt caused during the war. I would welcome if Teachta Martin said “This is Sinn Féin” but he uses sleveen, sleekit, weasel words such as “It appears to be Sinn Féin”, “As far as I can see”, “It appears to me”, and “As far as I have been able to ascertain”. Let me be very clear about this; all the victims deserve justice – every single one, particularly the victims of the Irish Republican Army. I say that as a republican because I cannot rail against injustices inflicted by the British or others if I do not take the same consistent position in terms of those who were bereaved by people whose legitimacy I recognised. Both the Taoiseach and the leader of Fianna Fáil recognised the legitimacy of the IRA cause, but in another decade. Somewhere along the line they became revisionist on the issue. I wish to be very clear that, first, it is the right thing to do morally; second, it is the right thing to do for the peace process and; third, I understand because I am from that community. That is where I come from. […]

Deputy Micheál Martin: […] I wish to make straight remarks and not weasel words. One of the questions I put to the Taoiseach was that the past is a key issue, but what is going on right now with regard to the past is, in my view, reprehensible. A hate campaign has developed against those involved in the Boston exercise. Those involved, those who did the taping and contributed to the tapes, genuinely believed they would not be released until after the participants were dead. Sinn Féin has an issue with this as do others but it is unacceptable that on the front page of the Sunday World one reads that ‘Boston tout’ Ivor Bell is under pressure to ‘come clean’ on the contents of the controversial Boston tapes.

There is graffiti now on the walls in the North about the touts, the informers and the greed. The salaries of those who actually did the interviews is out as though it represents some astronomical amount of money and that it was all for greed. Comparisons are being made between those who were involved in the project and those who cracked under pressure in Castlereagh and became informers and who were dealt with by the then IRA.

One gets good cop and bad cop all the time. On the one hand, one gets the nice presentation but on the other hand, this is going on right now. I have been contacted about this and people are worried about their lives. People are worried about the security aspect to it. It should be condemned and Sinn Féin should make sure that anyone associated with the party who is involved in this regard should stop and cease, no matter how uncomfortable or inconvenient it is. While the leader of Sinn Féin will accuse others of revisionism, I put it to the Taoiseach that it is absurd revisionism to suggest that any just war was going on over those 30-odd years from 1974. Many ex-combatants would say there was no justification, in retrospect, for anything that went on after Sunningdale. There was no great war, there was a war and terror and people were killed who did not need to be for far too long. It went on for years and years and now we all are being cosied to accept language around conflicts, war, sides and all that. Too many appalling atrocities were carried out that cannot be justified in any shape or form.

Moreover, I make the point to the Taoiseach that the peace process belongs to the Irish people, not to the Taoiseach, to me or indeed to the Sinn Féin Party. Yet, when someone gets arrested who the Sinn Féin Party does not like getting arrested, its members will organise protests outside the police station as they did in the case of the prominent arrest of one of its members with regard to the McCartney murder, when 300 people turned up outside a police station and when a member of the policing board, namely, Gerry Kelly, said this was an outrage. When they want to threaten the peace process, they will do it. The same happened in recent weeks, because Sinn Féin did not like a particular arrest. The peace process now was under threat and policing support was under threat. One cannot have it both ways; one either supports it or one does not. One cannot just switch up, switch off or switch down the temperature when it suits and the temperature was switched up deliberately two weeks ago. No one should be under any doubt or illusion about that. The mask slipped for a few days but it did so deliberately. The word to the authorities was were they to keep going, they would not have a peace process. Were they to keep going, they would not have support for policing in Northern Ireland. […]

Deputy Gerry Adams: Briefly, and I wish to come back to the Taoiseach’s remarks, no one involved with Sinn Féin is engaged in the graffiti, the wall daubing or the perceived or real threats against anyone. This is extremely clear and I condemn these threats and everyone has stated more times than enough that people must be able to go about their business without any fear of any threat whatsoever. Moreover, for the information of Teachta Martin, the Haass proposals include the right of families to seek legal redress if they wish and Sinn Féin supports that concept. One must understand here that there are multiple narratives. In the same way as there are the Fine Gael, Labour Party and Fianna Fáil narratives, in more recent times there are the Sinn Féin and the republican narratives, as well as Unionist, British Army and IRA narratives. We would get some sense of our history were we willing to lay all those narratives side by side as opposed to undermining any of them. Moreover, for the record, no generation of the IRA had a mandate, not in 1916, not during the Tan war and not during the Civil War or since. However, every generation of the IRA had sufficient endorsement of enough people to continue, including in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s until thankfully, the war was brought to a close. […]

The Taoiseach, Enda Kenny: […] I must state that when I saw the people presenting and preparing the mural of Deputy Adams in Belfast, as is their right, comments were made there by some people to the effect that “We have not gone away“. Who are the “we” and to whom they were referring when they said “We have not gone away”? These clearly are supporters of Sinn Féin and I am unsure what interpretation to put on this. I hope we can move this forward. Certainly, I assure the Deputy that from the point of view of the Government, there certainly is no lack of interest in this regard. Both Governments will be happy to co-operate with, work with and encourage the parties if they can see there is an opportunity to move forward any of these issues to a point where a better outcome can be achieved.