An American oral history project makes us fear for our lives, say former IRA members

By Jenny McCartney

The Telegraph

May 15th, 2014

If you want to know whether fear of IRA reprisals remains a powerful force in Northern Ireland, look no further. A former IRA prisoner, Richard O’Rawe, along with three others, is suing Boston College for its failure to protect confidential interviews about his time in the IRA. He is doing so, he made clear, because of the intimidation he has now endured as a result of going on the record.

The interview was recorded as part of the Boston College project, launched in 2001, an oral history project which recorded a large number of interviews with former members of the IRA and loyalist paramilitaries. Participants were assured that the material would only become public posthumously or with their permission.

In fact, Northern Irish police investigating the murder of Jean McConville, a mother of 10 abducted, killed and “disappeared” by the IRA in 1972, won access to ten of the recordings following a legal battle which went to the US Supreme Court. The project was linked in many reports to the recent arrest and questioning of Gerry Adams.

Mr O’Rawe is arguing that since Boston College allegedly did not warn him of this possible outcome, he has suffered “serious intimidation and distress together with reputational damage as is evidenced by recent widespread graffiti appearing in West Belfast.”

The experience of “intimidation and distress”, of course, has been shared by the organisers of the project, Dr Anthony McIntyre, a former Provisional IRA member himself, and the journalist Ed Moloney, both of whom opposed the handing over of the tapes.

Dr McIntyre in particular – who lives with his family in County Louth – told one newspaper that “the hate has been ratcheted up since the Adams arrest.” Among other things, he said that “Danny Morrison [the former Sinn Fein publicity director] has labelled us ‘touts’”.

For those not versed in the parlance of Northern Ireland, “tout” is a uniquely dangerous and toxic word. The label of “tout”, ironically, was exactly the term that the IRA originally used to justify the murder and disappearance of Jean McConville in 1972 (a subsequent police investigation found no basis for its accusation).

During the Troubles, the IRA “punishment” for so-called “touts” was death. Even throughout the “peace process”, indeed, the IRA murdered, or attempted to murder, individuals whom it accused of being “touts”, with barely a squeak of protest from the British or Irish governments. In 1999 it killed Eamon Collins, an emotionally complicated former Provisional IRA man who had written a book called “Killing Rage” which exposed the squalid inner workings of the IRA and his own conflicted relationship with the organisation. It inspired fury within the IRA. Graffiti went up on walls, and one day Collins – who had stubbornly continued to live in Newry – was found battered to death in a ditch.

In the same year, the former police agent Martin McGartland, who had infiltrated the IRA, narrowly managed to survive an IRA attack in England in which he was shot six times at close range.

McIntyre does not share a similar history to either man, but – even though he and Moloney vocally opposed the handing over of the Boston College archives – by its very existence the project has clearly challenged the omerta around IRA activities which Sinn Fein wishes to remain.

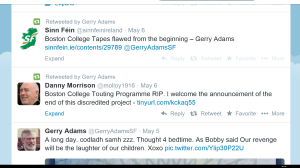

The application of the word “tout” to the Boston project has been implicitly endorsed by those at the party’s very highest level. In between the photographs of ice creams and rubber duckies which feature heavily on his Twitter feed, Gerry Adams retweeted Danny Morrison’s remark: “Boston College Touting Programme RIP.” The official signal to supporters of how the project should be viewed will not be missed.

I understand the desire of Jean McConville’s family to have access to evidence that might establish who was responsible for her murder. I also understand the desire of McIntyre and Moloney to protect their sources. The former is about the delivery of justice, the latter about the urge to establish and safeguard historical testimony in contentious circumstances. In this instance, the two things have been placed in direct opposition: the problem with this particular historical project has been that the history is still live. Boston College has now reportedly offered to return the tapes to the participants: historical record will be the poorer for it.

My political views undoubtedly differ from McIntyre’s in a number of fundamental ways, but I believe he is correct when he says that the Boston project offered “an alternative to the political and legal fiction constructed for its ability to facilitate the peace process rather than produce accuracy.” I also suspect that there are allegations within those tapes which would be embarrassing, not only to the IRA and the loyalist paramilitaries, but to the British government. And I believe that he and his family have a right to live free from fear and harassment.

Martin McGuinness recently said that he believes Gerry Adams when Adams says he was never a member of the IRA: with the official Sinn Fein view of history, we are quite clearly now in the heady realm of the surreal. The Sinn Fein leadership, in fact, has proved consistently hostile to any former IRA members who challenge its version of history, which is commonly defined by a combination of selective denial and airbrushed sentimentality. Yet what have we seen and heard in recent weeks, when Sinn Fein was rattled by Adams’ arrest?

Bobby Storey, an alleged former IRA intelligence director, told a rally in West Belfast “we haven’t gone away, you know” (echoing the famous 1995 Adams line about the IRA). Michael McConville, whom the IRA beat and threatened into silence about his mother’s abduction when he was a terrified 11-year-old, said that as an adult he had told Gerry Adams the names of those who abducted his mother and Adams had personally warned him to prepare for a “backlash” if he made the names public. Mr McConville understandably said: “I took it as a threat”.

The IRA called Mrs McConville a “tout” in 1972, and we saw what human misery flowed from that. Today the Sinn Fein leadership is knowingly calling those involved in the Boston project exactly the same name. The words “Boston College touts” and “In-former Republicans” have appeared on walls on Belfast’s Falls Road, echoed without censure on Adams’ Twitter account.

They are not there by accident: everyone involved, including Adams, is acutely aware of the historical charge such names carry. As the Sinn Fein president canvasses for the European elections, glad-handing passers-by in the sunshine, surely voters, academics and journalists alike should ask him publicly to condemn any threats that lurk in the shadows against those involved in the Boston project. Otherwise, one might draw the conclusion that Adams is perfectly at ease with them.

Jenny McCartney is a columnist for the Sunday Telegraph. On her blog, she offers hard-hitting analysis of social and political concerns and a witty deconstruction of modern celebrity culture.